Module 1: MOUD 101

Unit 4: Client Centered Approaches

MOUD & Client Considerations

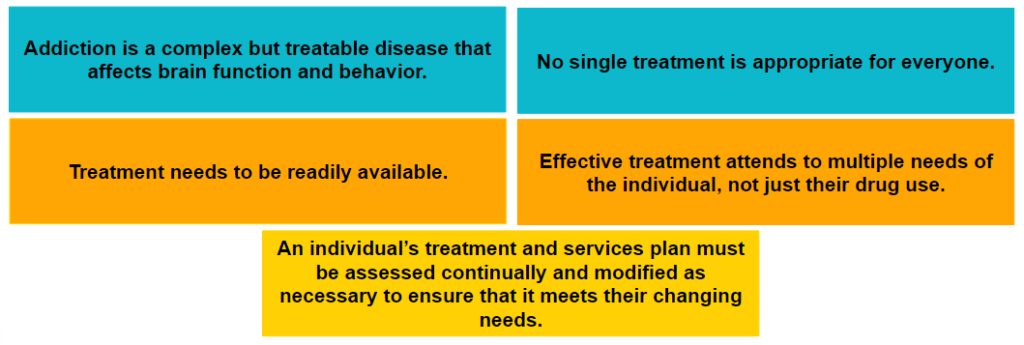

Addiction Treatment Principles The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, 2020) is guided by 13 treatment principles as it relates to addiction, treatment, and recovery. We share five principles below to stress the importance of empathy, flexibility and support when working with clients on MOUD.

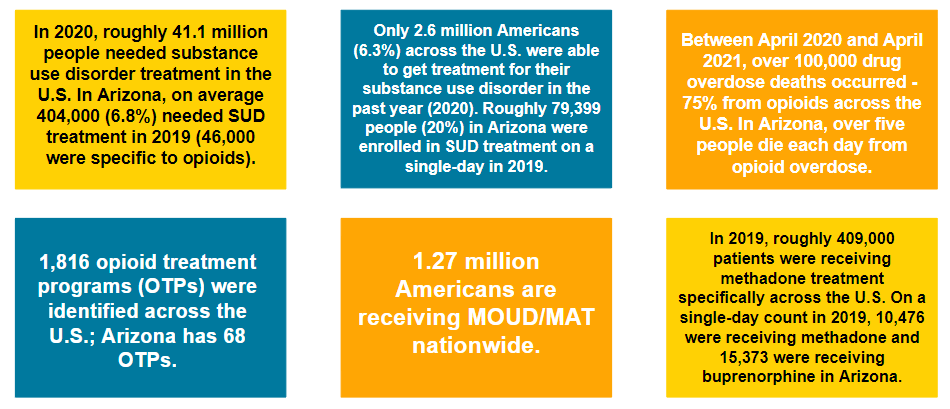

Impacts of Opioid Use Disorder

MOUD & Client Rights

It is illegal to discriminate against clients for MOUD use. In other words, recovery homes cannot deny services/housing simply because a client uses MOUD.

Federal protections for those utilizing MOUD generally* fall under:

- Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

- Rehabilitation Act of 1973

- Fair Housing Act (FHA)

- Workforce Investment Act (WIA)

According to these legal protections, individuals in recovery on MOUD are considered individuals with a ‘disability’ as they experience physical or mental impairment due to substance use.

*This is not intended to substitute legal advice. Recovery home owners should seek professional legal advice if they have further questions in this area.

MOUD & Client Rights

Recovery homes policies that prohibit storing MOUD such as methadone or buprenorphine can create an additional barrier for clients. Under the Fair Housing Act (FHA), residences must make ‘reasonable accommodations’ for individuals on MOUD.

Examples:

- Arranging for the individual to take medication at the outpatient treatment provider or physician’s office, or another off-site location – when consistent with the individual’s treatment plan.

- Storing an individual’s MOUD medication in a lockbox in the house and having the individual be personally responsible for it or arranging to have the housing facility keep MOUD medications in a locked cabinet.

MOUD & Client Rights

Clients have a right to safe, supportive housing. Clients can file a grievance or complaint if they have experienced mistreatment or discrimination.

File a grievance with AzRHA online:

- Those who live in a recovery home certified by AzRHA can file a grievance online: https://myazrha.org/file-a-grievance

File a charge or civil action:

- Southwest Fair Housing Council: https://housing.az.gov/have-you-been-discriminatedagainst-when-making-your-housing-choice

Client Centered Approaches

People experiencing homelessness

Facts and stats:

- Approximately 568,000 people experienced homelessness on any given day in 2019.

- Those experiencing homelessness and SUDs have fewer resources and social supports.

- Stable housing is such an important aspect of recovery – studies show clients are more likely to engage in MOUD if housing is secured.

- Abstinence-only policies in recovery homes can create further barriers for those in need of housing.

People experiencing homelessness

Recommendations:

- Housing providers & medical providers should collaborate to ensure a supportive housing model for clients on MOUD.

- Housing first model (housing no matter where a person is in recovery) is the preferred approach for individuals experiencing homelessness.

- Recognize that linear housing models (abstinence first and completion of SUD treatment before housing) tend to have low SUD program completion rates, adding barriers to housing.

- Consider bringing in medical providers to educate staff on MOUD and address myths.

Practice Scenario & Reflections

James is receiving MOUD for an addiction to OxyContin. His substance use largely stems from financial strain, when he lost his job and house in 2008. He is actively working on his recovery and is looking for a place to stay after he transitions out an emergency housing shelter. James recently applied for residence at a recovery facility but was denied because he was utilizing methadone as part of his recovery journey..

Take time to think about the following questions or discuss with your peers. There are no right or wrong answers…

- Do your policies and practices support the recovery of clients like James, or would you decline to accept him in your program?

- What are some of James’ legal rights as he seeks residence in a recovery home while on MOUD treatment?

- How does your house demonstrate understanding and support for clients who are making their way through multiple systems (health care, criminal legal system, etc.) and facing multiple barriers (transportation, securing employment, managing their MOUD and recovery)?

While the recovery population is diverse, some populations are at a particular disadvantage, dealing with intense fear, shame, stigma and lack of support because they have been historically underserved. Further, they can sometimes face ‘double stigma’ from peers in recovery who are not on MOUD. These barriers impact their recovery. Social and healthcare settings need to work together to ensure recovery is inclusive to all those who need it.

People involved in the criminal justice system

Facts and stats:

- Over half (58%) of state prisoners and sentenced jail inmates (63%) had drug dependence needs (compared to 5% of the general U.S. population).

- The first year of release from incarceration has the greatest risk of opioid overdose death.

- Some justice-involved individuals may have started MOUD treatment while incarcerated. It is important to have a supportive environment to continue treatment as it reduces barriers related to healthcare access and the odds of criminality.

- A supportive housing environment can bring some ease to the reentry and recovery process.

Recommendations:

- Housing providers can work with criminal justice and medical providers to help debunk myths and negative perceptions of justice-involved on MOUD – focusing on the link between homelessness, criminal justice and behavioral health.

- Housing environments can build a supportive culture by learning the link between recidivism, unmet behavioral health needs, and lack of stable housing. This can promote empathy among clients and staff.

- Housing managers can promote ongoing communication between clients and their healthcare providers, offering phone or internet-based equipment when needed and supporting technological equity (techequity). This simple gesture can help clients remain in treatment and build a trusting relationship between clients and staff.

Practice Scenario & Reflections

Melissa recently was released from prison after she was incarcerated for the possession of heroin. After previous attempts to gain sobriety, she found success while incarcerated after she began MOUD treatment. Melissa is looking for stability upon reentry to complete her probation requirements, obtain meaningful employment, and continue progressing in her recovery journey.

Again, think about the following:

- In what ways is your home/organization working with clients who are justice-involved to help them successfully reenter our communities?

- What common barriers do you see clients face in accessing health care and/or substance use treatment? How can your home help bridge these gaps to address barriers?

- What experiences have you witnessed with clients regarding the link between recidivism, unmet behavioral health needs, and lack of stable housing?

For additional client centered recommendations and reflections, see Module 2.

Key Takeaways

Client-Centered Approaches

- Only a small number of clients in need of SUD treatment are on MOUD.

- Clients on MOUD are protected under federal and state laws.

- SUD treatment is client-centered and varies from person-to-person.

- Safe and stable housing is an important aspect of the recovery process.

- Recovery homes could benefit from trainings that recognize the unique needs of their clients based on various intersecting identities to foster an environment that is supportive of their clients throughout their recovery journey.

RHAAZ Course Curriculum

Sources:

- Clients & Considerations Graphic: NIDA 2020

- Impacts Graphic: ADHS (2022); CDC (2022); HHS (2021); NHCHC (2021); SAMHSA (n.d.); SAMHSA (2019); SAMHSA (2020b)

- Legal Action Center (2019); SAMHSA (2019)

- Orlando (2021); Wyant et al. (2019); SAMHSA (2020a)

- Bronson et al. (2017); Ranapurwala et al. (2018); SAMHSA (2020a); Welch (2020)

- SAMHSA (2020a); Rowell-Cunsolo et al. (2021)